Focus on the Nordic and Baltic Sea

Looking at what is driving grid development in the Nordic and Baltic Sea region: integration of the Baltic power systems, enabling North to South power flows? Impact of planned nuclear decommissioning in Sweden and Finland?

What are the drivers of grid development in the region?

There are several drivers for grid development within the Baltic Sea region. Some relate to the current trends in the European energy markets and some to the specific characteristics of the region.

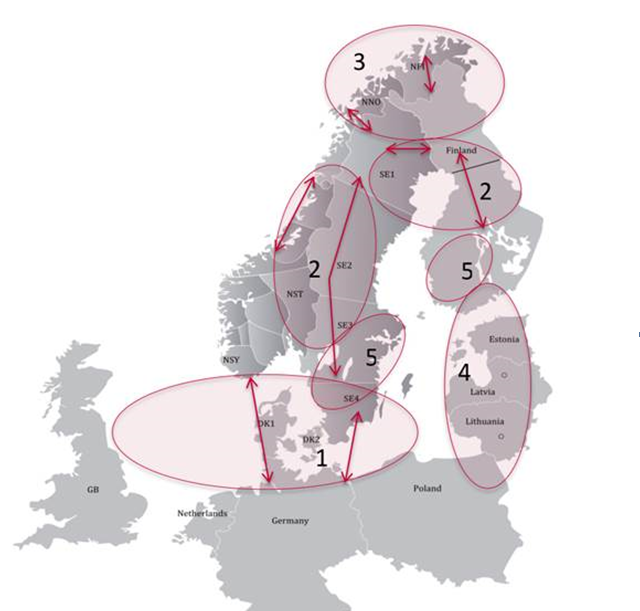

Figure 1 – Focus areas for grid development in the region

1. Further integration between Nordics and the Continent

The Nordic part of the Baltic Sea region is likely to still have an annual energy surplus by 2030, even if some nuclear is decommissioned, which would make it beneficial to strengthen the capacity between the Nordics, Baltics and continental Europe. Additionally, for daily regulation purposes, it is beneficial to connect the Nordic hydro-based system to the thermally based continental and wind based Danish system, especially when large amounts of renewables are connected to the continental system.

2. North south flows

The planned new interconnectors to the continent in combination with substantial amounts of new renewable production being built in the northern parts of the region is increasing the need to strengthen the interconnection capacities in the north-south direction in Sweden , Norway and Finland. In addition nuclear and thermal plants are expected to be decommissioned in both southern Sweden and Finland which further increases the demand for capacity in the north south direction.

3. Arctic consumption

Energy consumption in the arctic part of the region may increase due to new mining, oil and gas production facilities and server centres. This means that the grid will need to be reinforced in order to ensure security of supply in the area.

4. Baltic integration

To further integrate the Baltic States into the European market, enhance energy security, and decrease dependency on non ENTSO-E countries, the Baltic states need to be further interconnected to the Nordic and continental systems. This issue is described more deeply in the insight report “Baltic synchronisation”.

5. Nuclear and thermal decommissioning

A substantial proportion of Swedish and Finnish nuclear plants are expected to be decommissioned in the 2030 horizon. This would lead to an increased risk surrounding system adequacy.

What do the results of the TYNDP 2016 show for the region?

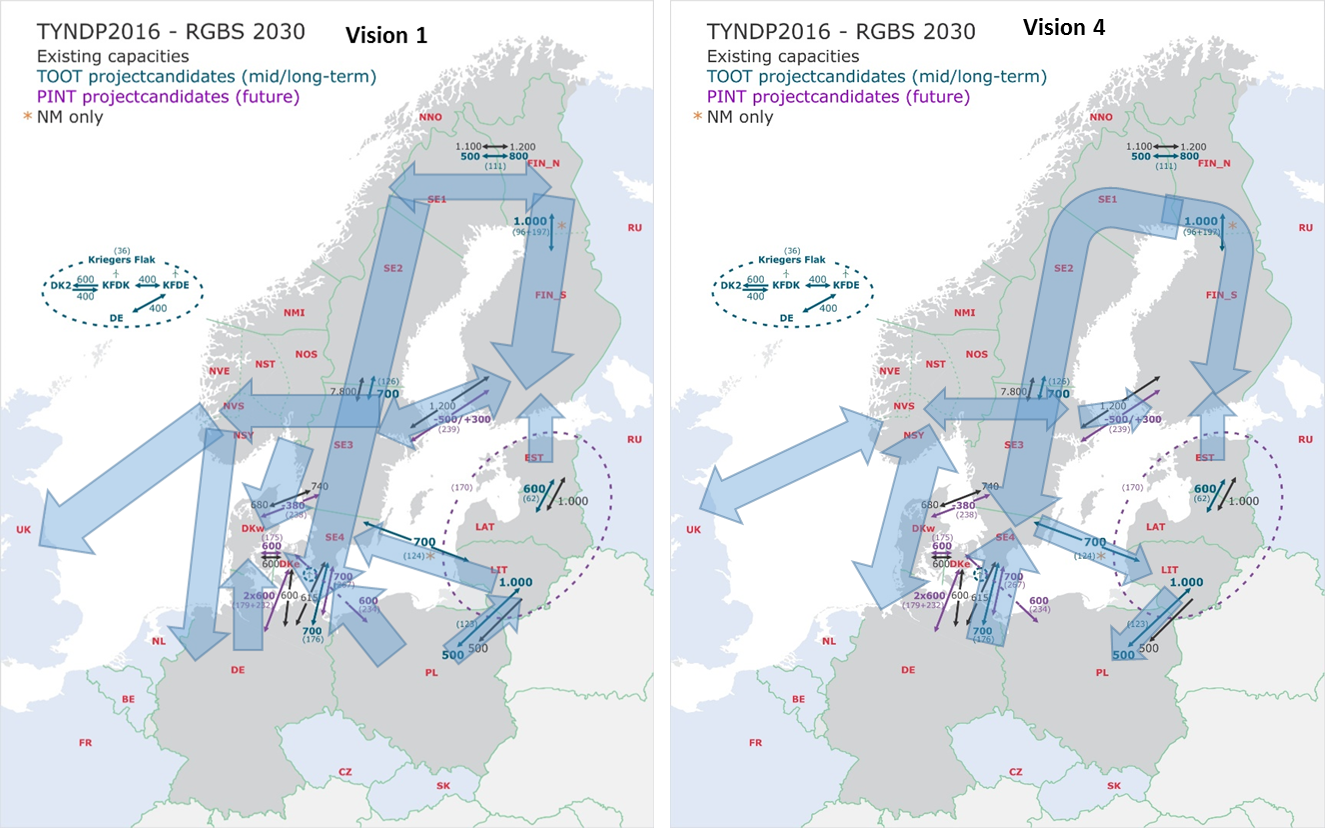

The project portfolio in the TYNDP 2016 is similar to the one presented in TYNDP 2014. Three new conceptual future project candidates were identified during the common planning studies (SE-DE, SE4-PL, DKe-DE and DK-PL). In addition, two potential future reinvestment projects (SE3-DK1 and SE3-FI) were included in the TYNDP 2016.

Flow patterns and energy balances shows great variation between the analysed visions where flows are mainly southbound in vision 1,2 and 3 where a large Nordic energy surplus is exported to the continent. In Vision 4, the net flow between the Nordic and continental system is low while interconnectors still have a high utilisation rate. This is due to that the flow is alternating because of the Nordic hydro reservoirs are used as a flexible resource to balance the high wind generation in Denmark, Germany and the United Kingdom.

Market studies show that that there is a value in increasing the interconnection between the Nordics and the continent regardless of whether or not there is a large energy surplus the Nordics. Indeed, the hydro reservoirs of the Nordic are used by Denmark, Germany and the United Kingdom as a source of flexibility to deal with variations in production of an increasing amount of renewable energy sources.

The added value of more interconnection between the Nordics and the continent is also supported by the TYNDP 2016 CBA analysis that shows high social and economic welfare (SEW) benefits for project between the Nordics and the Continent. See project sheets for CBA results for specific projects. Annual energy balances and bulk flows are presented in Table 1and Figure 2 below.

| Country | 2015 | EP2020 | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | -4.9 | -1.8 | -8.7 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 10.6 |

| Estonia | 0.9 | -2.5 | -3.1 | -6.1 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| Finland | -16.3 | -10.2 | -0.9 | -2.3 | -9.3 | -17.4 |

| Germany | 59.8 | 62.8 | 25.7 | -24 | -3.9 | 2.2 |

| Latvia | -1.8 | -1.2 | -0.7 | -1.1 | 4.3 | 4.4 |

| Lithuania | -6.3 | -8.6 | 0 | 0.8 | -3.9 | -3.4 |

| Norway | 16.7 | 11.6 | 11.8 | 18.5 | 8.4 | -2.2 |

| Poland | 2.8 | 22.4 | 23 | 16.3 | -31.9 | -27.7 |

| Sweden | 22.6 | 5.7 | 12.6 | 20.4 | 27.3 | 7.3 |

Table 1 – Energy balances in 20151 and in the future per scenario and country

Figure 2 – Bulk flows in Vision 1 and Vision 4

Why are there some differences between TYNDP and regional study results?

The TYNDP 2016 market studies were done on a pan-European scope and all regions used the same data for hydro inflow, wind and demand variation. Because of such a wide scope only one year of weather data was used in the studies.

This notably explains why the pan-European studies’ results differ somewhat with the results of regional studies that allow for a more detailed analysis.

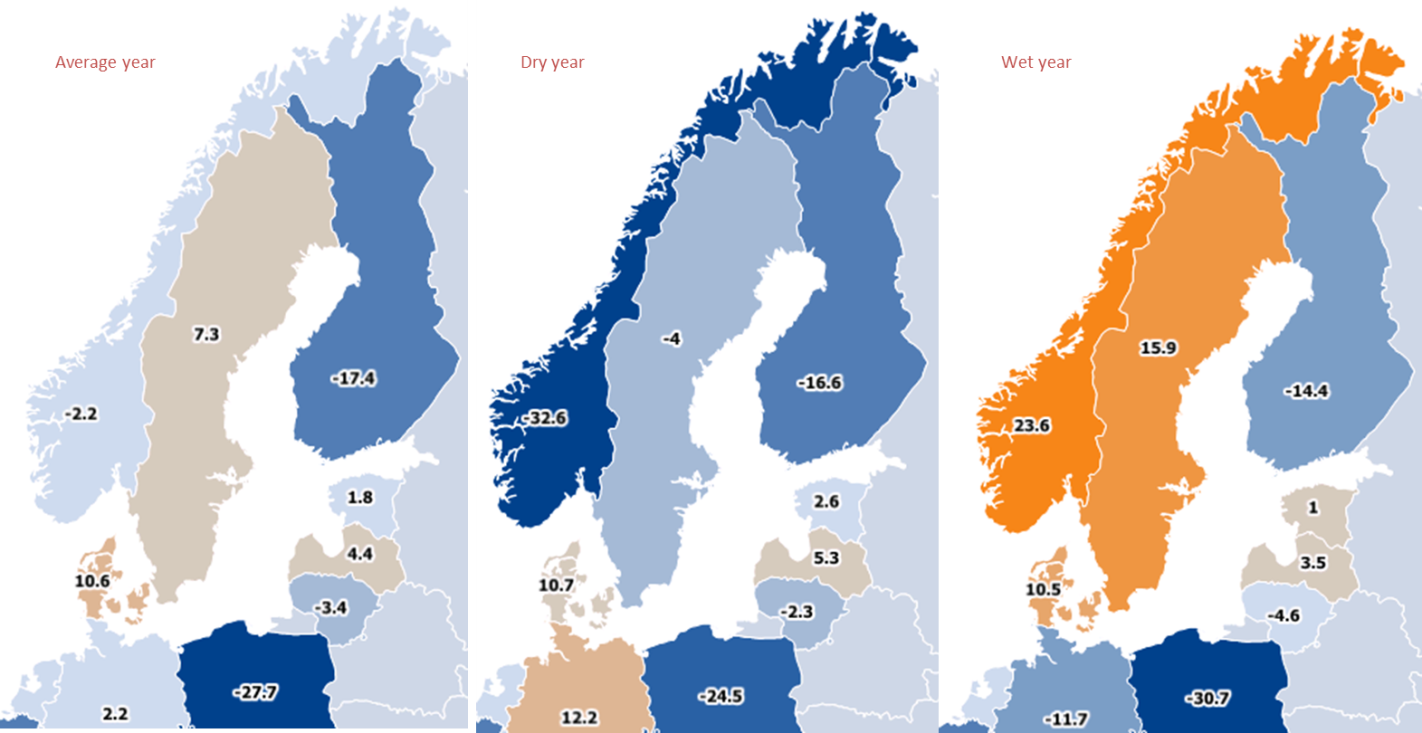

The most important cause for the difference in results is that the energy balance in the Nordics is very dependent on the hydrological conditions, which is illustrated in Figure 3 below.

The benefits of interconnection projects both within the Nordics and between the Nordics and the continent is typically higher in wet or dry years, hence the benefit of interconnectors within the region is typically underestimated when analysis is done on a normal year alone.

This partly explains why interconnection projects showing low or even negligible benefits in the TYNDP 2016 market study show higher benefits when more detailed studies is done by the regional TSO’s.

Figure 3 – Simulated energy balances in Vision 4 for average, dry and wet inflow year (TWh).

What are the other challenges the region is facing?

The energy transition is not only increasing the need for more transmission capacities. It also creates additional challenges for the power system such as generation adequacy, frequency stability and inertia. These challenges need to best addressed in a coordinated manner by the regional TSOs in order to find the most efficient solution. Regional cooperation is a real must. The Nordic TSOs are for example currently working together on a joint report, “Nordic challenges and opportunities”, on how to address these challenges and which is due for publication in August 2016.

Regional coordination of the TSOs will be tightened up through the creation of a Regional Security Coordinator in the Nordic and Baltics. The discussion for the Nordic RSC started in May 2016. RSCs are one of the faces of regional coordination of TSOs. Existing since 2008, they will roll out in Europe by end 2017. Their role has been officialised in the System Operation Guideline, a EU network code that should become EU binding law at the end of a legislative process called the Comitology process.

Generation adequacy

Substantial amount of nuclear and thermal production units in Nordics is expected to be phased out until 2030 and there are currently only a few plans for new non-intermittent capacity in the system. Analysis done by Nordic TSOs show that there is some loss of load expected in the 2030 perspective. It is not clear if the current market mechanisms will deliver the needed investments in peak generation capacity and/or demand side response.

Similarly, in the Baltic States, a number of old thermal units are scheduled to be decommissioned by 2030. Some of the units come to the end of their technical lifetime and some do not comply with the Industrial Emissions Directive. There are no approved plans for considerable new non-intermittent generation capacity as the current power prices are too low for new investments.

Frequency stability

The frequency quality in the Nordic synchronous system has been declining since the deregulation of the electricity market. There are several reasons for this such as high ramping rates of interconnectors to the continent , volatile wind production and ramping of production around hour shifts (due to hourly based day ahead market).

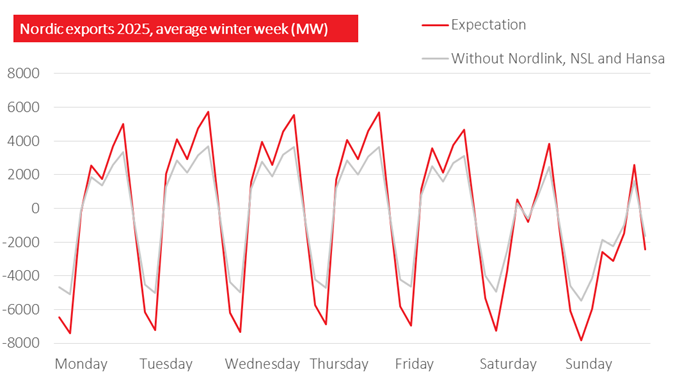

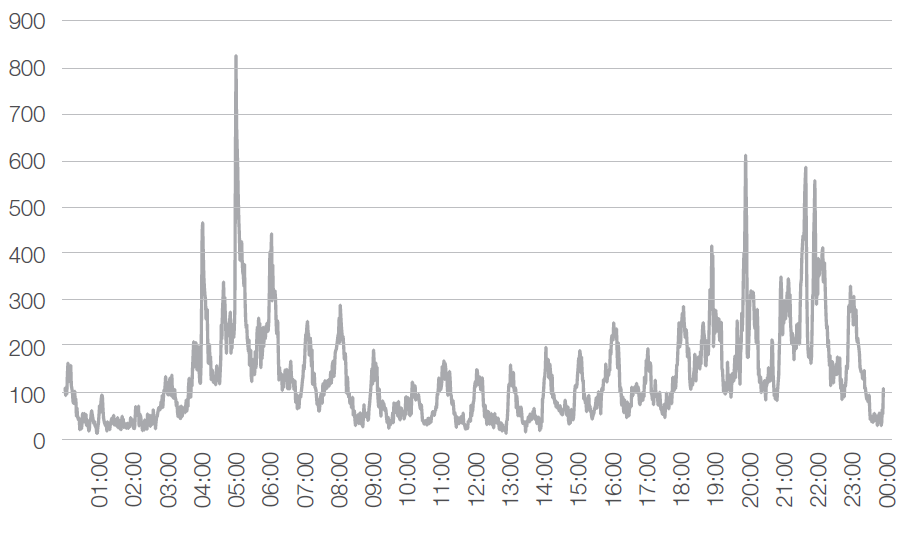

Figure 5 shows the amount of frequency deviations in the Nordics synchronous area, which is concentrated around hour shifts. Towards 2030 additional interconnectors and RES production is planned which means that ramping rates will increase further which may put an even higher strain on the frequency stability. Figure 4 below shows the increasing exchange to and from the Nordic synchronous area because of planned new interconnectors.

The regional TSO:s have to cooperate to implement technical solutions such as improved automatic reserves as well as improve the market design so that it supports the system operation in a better way.

Figure 4 – Interconnector flows to and from the Nordic system2

Figure 5 – Frequency deviations in the Nordic system3

Inertia

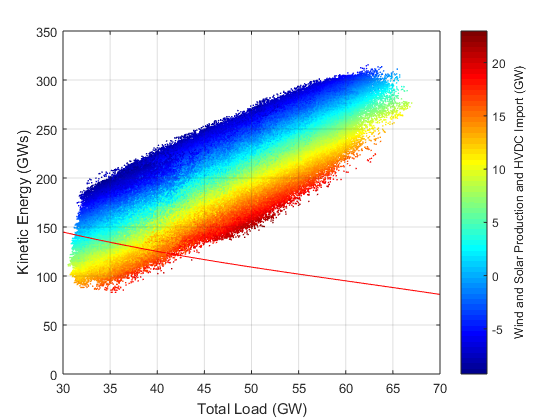

Another reason for why the frequency stability may deteriorate further in the future is that amount of inertia in the system is expected to decrease. The amount of inertia in the system determines the immediate4 effect on the system frequency of a trip of a large production or consumption unit i.e. Nuclear block or HVDC interconnector. The inertia decrease is caused by the shift from nuclear/thermal production to RES production since that RES production is not contributing to the inertia5 of the power system the same way as Nuclear and thermal plant does. This creates issues in low load and high RES situations where the remaining synchronous generators might not contribute adequate amount of inertia. The figure below shows that the amount of inertia in the Nordic system in year 2025 might not be sufficient in low load and high RES production situations. Since lack of inertia could compromise system stability, other sources6 of inertia may have to be introduced in the future.

Figure 6 – Estimated kinetic energy in 2025 as a function of total load in the synchronous area with wind and solar production and HVDC import including all climate years (1962–2012) of the market simulation scenario. The red line shows the required amount of kinetic energy7

The low inertia situation may occur also in the Baltics when the Baltics should switch to an island operation system with only HVDC interconnectors connecting the neighbouring systems. Significant amount of thermal capacities is planned to be decommissioned, however considerable large capacity of wind power is under development, which do not support the system with inertia. In case of this scenario, additional sources of inertia may have to be implemented in the Baltics, as well.

ENTSO data portal ( https://www.entsoe.eu/data/data-portal/Pages/default.aspx) ↩

See the report “Challenges and Opportunities in the Nordic Power System” ↩

See the report “Challenges and Opportunities in the Nordic Power System” ↩

The inertia of a power system can be translated to the kinetic energy from all the synchronous spinning generators in the power system. Compare with using the same force when trying to break a heavy and a light spinning wheel. The effect on the speed (frequency) will of course be much greater on the lighter wheel when the same amount of force is used. ↩

Spinning wind turbines has an amount of kinetic energy but since they are currently not synchronously connected to the grid they do not contribute to the inertia of the system. However there are potential technical solutions to use the kinetic energy of wind turbines as inertia in the future. ↩

Synchronous compensators, and running synchronous generators on minimum production is sources available today and in the future “synthetic inertia” solutions that uses the inertia of asynchronously connected generators such as wind turbines could be implemented.. ↩

See the report “Challenges and Opportunities in the Nordic Power System” ↩